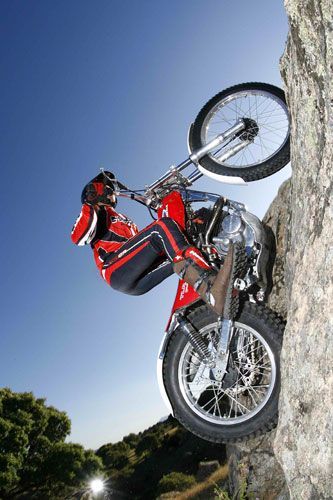

It is curious that in a speciality as homogeneous as trial, where fast and agile mechanics are sought, Honda bet heavily on four-stroke engines at a time when motorcycles with leaky cylinders dominated the specialty.

Honda’s obsession with the 4T does have a reason. Technical research has always been the workhorse of Soichiro Honda, the brand’s chief executive, so he thought that involving his models in high competition would help him develop the engineering of his products at the highest level. Soichiro retired in 1973, leaving the company in the hands of Kiyoshi Kawashima.

From that moment on, he devoted himself body and soul to the Honda Foundation, which had as its Objective: To achieve harmony between technology and respect for the environment. Consequently, within the technical racing department (HRC), different prototypes with eco-friendly four-stroke engines have always been present in any specialty.

Lejeune and the 4T

There was also speculation about a young man who, on the back of a Beta TR34, was revolutionizing the areas of the world championship with his aerobatic piloting. That young man, who would later become the best rider in history, was none other than Jordi Tarrés.

In 1988 Honda decided to completely disassociate itself from the world championship to focus on two-stroke engines. As a result of this great work, emblematic models such as the Cota 309 and 310 were born; the 311, with an aluminum chassis and hydraulic clutch option; or the 314R, which was the prelude to one of Montesa’s most ambitious and successful prototypes: the Cota 315R.

Later, in 2005, after a glorious period backed by the world titles of Colomer and Lampkin, the brand with the golden wing, encouraged by the severe environmental restrictions that plague us today, He was once again facing the same challenge of two decades ago: to create a 4T capable of defeating the Goliath of the nineties, the 2T.

Honda TLR. Fruitful

“Use under normal conditions.” This was the advertising slogan with which Honda promoted the TLR 250 in 1982, a particularly fruitful year, as Lejeune would win his first world title and a creditable third place in the Six Days of Scotland.

Based on the RTL 360 with which Eddy won the World Championship, Honda decided to manufacture, under the pseudonym TLR, two practically identical versions that would mark a before and after in the brand: the 200 and the 250.

Up until now, the trial slings that were imported from Japan left a lot to be desired in terms of aesthetics and performance. These four-stroke engines, which reminded the English of their ancestral large-displacement motorcycles, were usually transformed to the limit to make the most of their discreet performance.

The TLR 200 turned out to be an example of a practical, reliable and economical bike. The low consumption of its 4-stroke engine, together with the perfect staggering of its six-speed gearbox, made the small 200 perform with impeccable dexterity among the pack of two-stroke motorcycles that dominated the market.

Although the resemblance to the TLR 250 is undeniable, the latter has the features of a more professional and specialized bike. Its engine, more advanced and compact than that of the 200, offers that extra dose of torque and power that so limited its little sister in the most compromised areas; But all that glitters is not gold, as it is also more demanding with the pilot.

It was electronics. Montesa Cota 4R

T

Today, more than thirty years later , the Cota 4RT maintains the maxims that made the TLR range a benchmark in the early eighties: technology, ecology and reliability.

Going into the direct comparison of these models, what is most striking at first glance is, logically, the aesthetic evolution.

Over the years, the lines have been smoothed; The small padding that served as the seat eventually disappeared, the rear suspensions are longer and the fuel tanks have reduced their capacity by almost half. There has also been a proliferation of the use of lighter materials, such as carbon and aluminium, which were prohibitive at the time; Even the plastics that make up the body are now more flexible.

Surprisingly, the overall measurements of the bike remain virtually unchanged. The TLR has an overall length of 2,030mm, just 25 millimeters more than the 4RT and the same as a Scorpa 4T; while the wheelbase is virtually identical to any modern bike. In fact, if it weren’t for the fact that the footpeg anchor is higher and the seat a hundred millimeters below, we could say that the general metric of today’s motorcycles maintains the same canons.

The first big difference is in the start-up. A symbol of the electronic age, the 4RT features an advanced injection system that does not require any manual actuation; simply Follow the lever gently from above and keep the throttle grip closed. The TLR, on the other hand, starts 2T style. All you have to do is lift a comfortable cam on the carburetor and give a small hit of the gas while turning the lever. The TLR is, even with the gear engaged, surprisingly effective in this area.

Same Background, Different Shape

The engines have already come to life, but it’s hard to believe.

Thanks to the low purr of its valves and the perfect synchronism of all the components, we could even dare to measure its pulsations. They are like real Swiss watches.

Nor has the feel or sound of mechanics changed, which, at the slightest hint of the throttle fist, awaken from their slumber with a deep roar – although the TLR is much quieter – and begin to rev at a dizzying pace. The form has changed, but not the substance.

Honda engines offer textbook low-speed handling. This allows the pilot to easily predict their reactions and only worry about enjoying themselves within the zones. They are engines that seem to have no end, they endure the over-revs extraordinarily; However, the best secret to driving them is to make the most of the low rev range and inertia of the terrain.

The arrival of the Liquid cooling has been another great oxygen cylinder. The high temperatures that reach these 4T, together with the Low airflow received by trial bikes within an area, it reduces the performance of classic engines at times of greatest effort; Now that doesn’t happen, the fan makes sure that the temperature of the motor remains constant from the first to the last minute.

Another component that has evolved the most in recent years has been the clutch. According to the story, Lejeune was the end of what we know today as the “classic trial”. Back then, the use of the clutch was less intensive.

Chronologically, it coincides with the Belgian rider’s last stint at Honda, in 1986, when a small series of the RTL 250S in “Rothmans” colours, the first Honda trial bike with a monoshock – as you know, it is a prerequisite for the bike to have a double shock absorber to participate in a current classics series.

Although the clutches of our protagonists attend to two completely opposite worlds, we can say that they coincide in one aspect: speed. The clutch of the 4RT , as with its predecessor, the Cota 315R, is very sensitive in the last third of travel. On the TLR, more than a clutch, the left lever on the handlebar acts as a switch: it’s “everything” or “nothing”. The clutch of the “two and a half” did not inherit the progressivity of the “two hundred”, which is why some pilots of the time made small modifications. Chatting about the problem with Mike Andrews, he told us: “We modified the inner clutch cam, giving it more curvature. In this way we gained much more progressivity. Some of us also chose to place two gaskets at the base of the cylinder to finish smoothing out the response.”

Text: David Quer / Photos:

P. Soria

{bonckowall source=”2″ pkey=”album” pvalue=”dqtrialworld” pvalue2=”Honda4T Story” }{/bonckowall}